After a turbulent boat ride, I found myself climbing on the planks on stilts based on the coral reef. These were the streets of Sampela, the village where the sea nomads have settled. P., my host, smiled and immediately showed me the hut I would live in: two rooms, one mattress and one lamp, and a toilet that had direct connection to the sea. If you step heavily on the thin planks you can also find yourself in the sea. P. runs this business since he is one of the few who can speak English.

“Do you want beers?” He says, “My wife and child are going to the shore to bring water.”I nod yes. I explore my hut.

“How big is your village P.?” trying to start a conversation. “about 500 people… There are two other Bajau villages nearby” (Bajau population is currently estimated at 800,000, most of which now live permanently in villages).

“All the villages are over the sea?”

“Of course,” he says, “You know, Bajau don’t like mosquitoes.”

“And there are no mosquitoes here?” “For mosquitoes to come there must be plants. You cannot find plants over the sea!”

“Do you live all year in the village?” “My father goes for months at a time on large fishing boats, but I think it’s not worth it.” “Have you travelled to anywhere, for example to Java?” “Yes,” he says, “I’ve been to Germany. A German TV channel made the expenses! A guy came to shoot a documentary in Sampela. And then, he invited us to Munich, me as an expert swimmer and a veteran Bajau as an expert freediver. “” How did you find Germany? ” “Cold,” he tells me. P. does not waste his words.

I started a reconnaissance walk. “Step at the centre of each board, which has support, otherwise it may be rotten and you fall.”

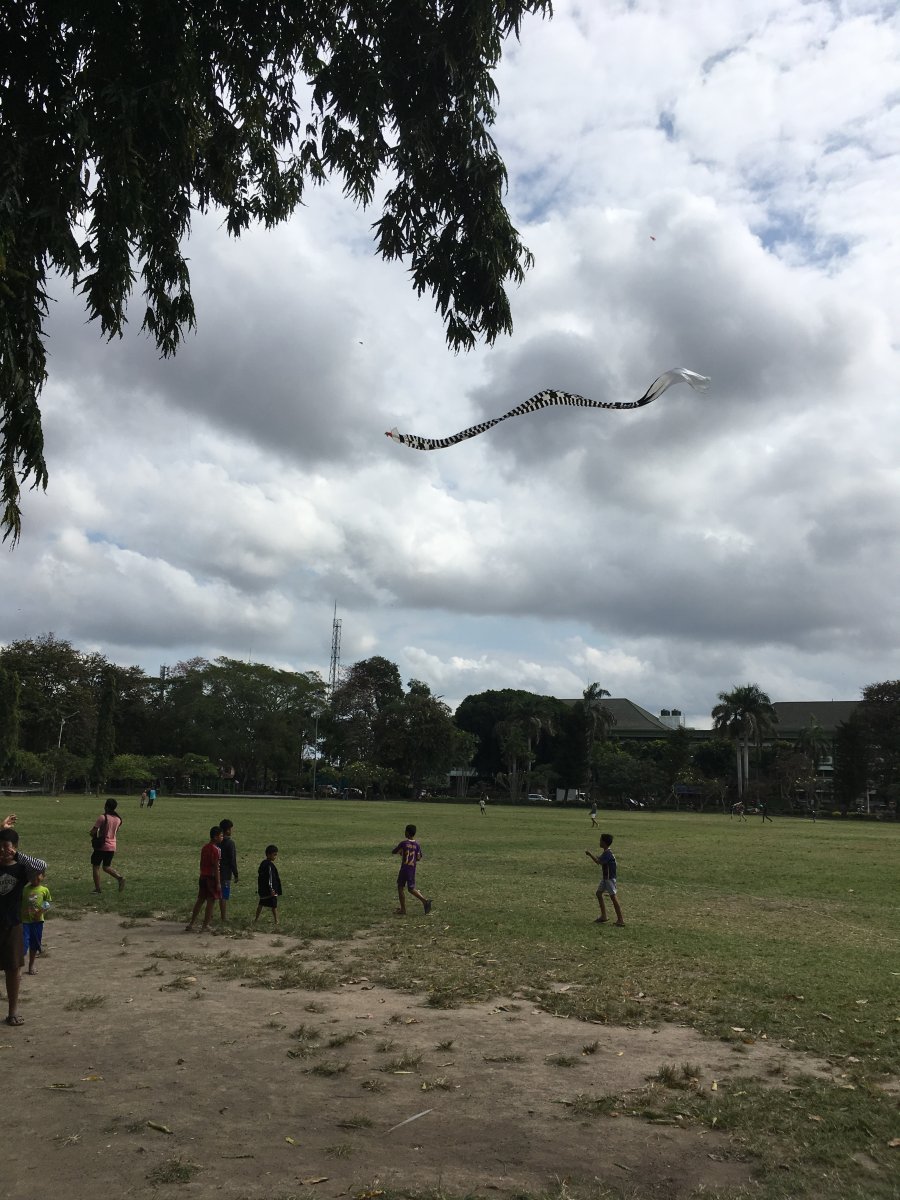

- Bajau children were amongst the happiest you’ll meet

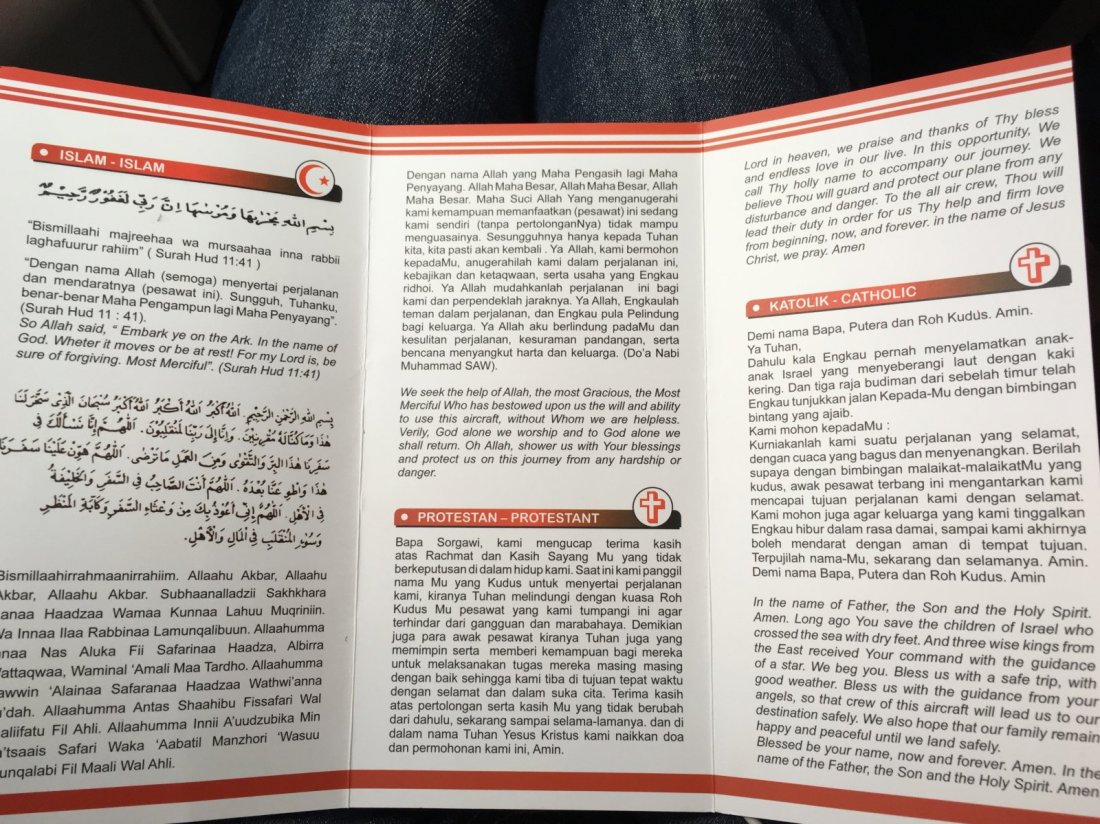

With a bunch of kids following me, we reach the courtyard of the mosque where small kids kick a ball. Yes, there is even mosque on the reef! P. told me they are all Muslims, but not too passionate, I realised from the context.

P. arrives and shows me around: “Here’s the school.” “Oh, yes, I’ve heard about it. The children of Hoga come here with the boat.” He lowers his head, “Do you see these beers in the school yard? You get the idea… “. We arrive at the football pitch the Dutch lady H. built in the most central point of the village. The court is small and they play footvolley, picking up occasionally the ball from the sea. P. proudly recommends to his teammates the Greek, who however proved to be a poor representative of the football of his country.

Next day there was a spear gun waiting outside my door. We were going to catch daya (Bajau word for fish), after a short visit to sign the village’s guestbook. Together with one of P.’s friends, we rode the boat to the coral between Sampela and Hoga. There, I became a witness to the Bajau underwater fishing technique. Majestic seen from above.

The technique is learned by every male Bajau from the first moments of his life since the tradition is to throw babies into the sea until someone dives to save them. Here a Bajau filmed for a BBC documentary:

P.’s friend gives me the spear gun to try my luck. A few minutes later and some unsuccessful attempts, I hear noise from the surface and P.’s friend grabbing my spear gun and hiding it under the coral. We go out, to see a boat next to ours and P. talking to two guys. A chubby one with glasses, not very comfortable being on a boat, and another one with rough features. “You,” says the second, “What are you doing with the speargun here? Don’t you know it’s a national park? “. All eyes on me. “I was snorkeling,” I lied, to save myself, but also not to put P. into trouble. Bajau is a very marginalised society, completely dependent on fish, which have become scarce because of the large fishing boats. P. opened the holds and showed that we have neither spear guns nor fish. “We saw you with the binoculars” said the spectacled one. “And in order to snorkel here, you have to get a ticket for the National Park.” Again, I was surprised. “The ticket…..”. “Get off to the shore” he said angrily.

The closest land was Hoga. The tide had begun to rise, and so we had to leave the boat and walk with P. a 500 meter distance in the water. A shameful walk. We found the two guys chatting with the Dutch lady H. while the bungalow residents were observing with curiosity. After some discussions, H. proposed a compromise: we’ll pay for the ticket, the pricing of which had become a bit creative, so that everyone realises it was a misunderstanding.

Back to the boat, we searched underwater for the spearguns and found them. P., who was both apologetic and angry with the water police, began telling me a story from his student years in Kentari. Some people were bullying him, because he did not smoke (indeed, P. must be the only Indonesian I knew how doesn’t smoke) and two machetes had appeared. “These conflicts never end up well” he concludes, showing me a scar in his leg.

P. had caught a fish. “Do you eat sushi?”, with a knife he cuts the raw fish into bits. He ate one, put another in his hand and offered it to me. “Try it.” It was not bad, with all this walking in the water I was hungry. “You are on the right track to become a Bajau,” he tells me and we laugh.

My time with the Bajau was soon over.